Bhagavad Gita – synopsis

November 23, 2017

Gita Chapter 2. The Practice of Yoga

November 28, 2017Namaste. Welcome to the Bhagavad Gita. It is my great pleasure and honour to assist you in its understanding and practice. I am so happy you are here.

Notes from the Translator, Shanti Gowans

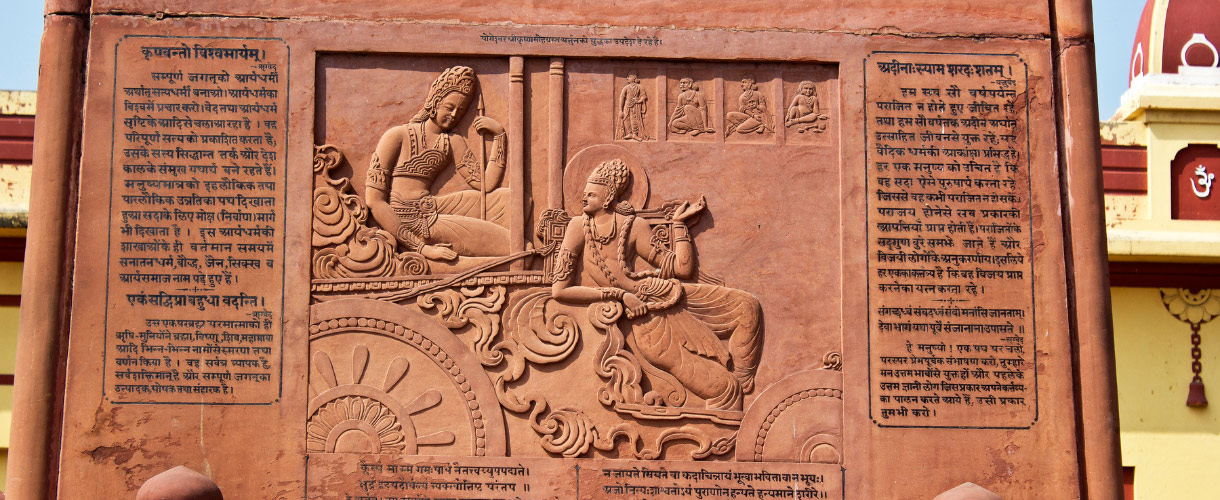

The Bhagavad Gita, literally ‘Song of the Lord’, is arguably the best known of all Indian literature. It is a 700-verse, Indian scripture, written in Sanskrit and recorded in the Indian epic, Mahabharata. It is set in the battlefield of Kurukshetra, which is fought between two rival families of cousins, the Kauravas and the Pandavas, Though it is composed of only seven hundred verses, it contains all the principles of the philosophy and psychology of the East. This information is not available anywhere else, not even within other religious scriptures.

The setting of the Gita in a battlefield has been interpreted as an allegory for the ethical and moral struggles in human life. The Gita’s call for selfless action inspired many leaders in the Indian independence movement, including Mohandas Gandhi, who referred to the Gita as his spiritual dictionary.

Indian traditionalists assert that the Gita came into existence in the third or fourth millenium BCE, around the ending of the Dwapara Yuga. The date of the Kurukshetra war and the delivery of the Gita to Arjuna, was supposed to have been around 3139BCE. Scholars have accepted dates from the fifth to the second century BCE as having been the probable range.

Numerous commentaries have been written about the Bhagavad Gita, with widely differing views about some of the essential ideology which sees them as different. They range from various views about the relationships between the Self and Brahman, namely the non-dualism of Atman and Brahman (Advaita vedanta), Atman and Brahman being both different and non-different, and that of different, or duality, (Dvaita).

Reading the Gita we come to better understand life as an inner battle, a struggle for the mind, heart, body and spirit…which is a fight to the death. We learn that our real enemies are not outside but within: our own passion, desire, greed and anger is what makes it so hard. These arch-enemies have linked forces so powerfully that they are all but unbeatable. We are losing. The Gita declares that spirituality is the only winning solution. Turn inwards, it directs us. Look no further than the true self within.

I will be teaching the Bhagavad Gita from the Vedantic, non-dualistic point of view.

There are eighteen lessons in the Bhagavad Gita, each describing a different aspect of the process of self-transformation. I will be teaching the Bhagavad Gita from the Vedantic, non-dualistic point of view. Firstly I will draw upon my knowledge of Vedanta from my lifetime of study, practice and experience as a meditation master, scholar and teacher. My aim is to teach you, the aspirant, how to establish equanimity both in your internal life and in your activities in the external world, to help you develop tranquility within and to explain the art and science of ‘doing’ actions skillfully and selflessly. I make no claims to having the most correct or profound understanding of this or any other Vedic texts, but I am confident that my interpretation does not stray from the path of truth. Secondly, I encourage you to experience the Gita directly through reflection and in your daily life. In this way, the study of the Bhagavad Gita becomes more than just an intellectual exercise; it becomes an inspiration for practice which can reveal the fundamental wisdom inherent within each and every one of us.

As much as possible, I have tried to translate the meaning. There are two different styles of translation. One of them is to translate each word literally and the other is to translate the meaning. As much as possible, and in my own style, I have tried to translate meaning. I hope that this translation of the Bhagavad Gita will satisfy your needs. Please enjoy this offering and may it be of service to you.

Overview of Chapter 1

1. Arjuna’s Despondency, Despair, Grief, Rejection – Arjuna Visada Yogam

Chapter one introduces the scene, the setting, the circumstances and the characters involved determining the reasons for the Bhagavad-Gita’s revelation.

The scene is the sacred plain of Kuruksetra. The setting is a battlefield. The circumstance is war, not withdrawing from life to meditate in some far-off cave, but how to live a more spiritual life today – more purposeful and fulfilling even while staying fully active in the world. The main characters are the Krishna and Prince Arjuna, witnessed by four million soldiers led by their respective military commanders. This chapter is about the philosophical dilemma faced by Arjuna.

The year is 3141BCE. Arjuna an esteemed warrior-prince, at the height of his powers, the greatest man of action of his time, is readying to go into battle. It is a righteous fight to regain a kingdom rightfully his. All his life he has been a courageous, successful achiever, renowned for prowess in combat. The chariot driver, Arjuna’s best friend from boyhood is Krishna, an avatar, an incarnation of divinity on earth.

Arjuna has requested Krishna to move his chariot between the two armies. After naming the principal warriors on both sides, Arjuna’s growing distress and dejection is described. It is an epic scene: two lone figures parked between the legions of good and evil; masses of soldiers, tents, cooking fires, neighing horses, banners flapping in the early-afternoon breeze, the bustle, noises, and smells of pre-battle fill the air. Arjuna’s eyes scan the opposing forces, pausing on former friends, revered uncles, teachers who taught him his warrior skills, all bravely making ready for the mutual slaughter. Because of the fear of losing friends and relatives in the course of the impending war and the subsequent repercussions and consequences attached to such actions, an off thing happens…his hands begin to shake, breathing unevenly, her slumps down and addresses Krishna…

This chapter, Arjuna Visada Yogam, The anguish of Arjuna comprises 46 verses.

Chapter 1: Arjuna’s Despair

Verse numbers printed within the brackets refer to the Sanskrit text.

CHAPTER 1: ARJUNA’S DESPAIR

King Dhritarashtra said, “Gathered on the sacred soil of Kurukshetra, the field of righteousness, eager to battle, tell me, Sanjaya, what did my children and the children of Pandu do?” (1)

The poet Sanjana said, “At that time, seeing the army of the Pandavas drawn up for battle and approaching his teacher, Dronacharya, Prince Duryodhana spoke these words: (2)

“Look at the mighty army of the sons of Pandu, arrayed for battle by your talented pupil, Dhrstadyumna, son of Drupada. (3)

There are many great warriors in this army, heroes wielding mighty bows and as formidable in military powers as Bhima and Arjuna: Satyaki and Virata and the mighty warrior chief Drupada. Dhrishtaketu, Chekitana and the valiant King of Benaris, Purujit, Kuntibhoja, and Shaibya, that bull among men, and bold Yudhamanyu. The valiant Uttamaujas, the son of Subhadra, Abhimanyu, and the five sons of Draupadi, all of them great warrior chiefs. (4-6)

O most honoured priest, look then also at the principal warriors on our side, the generals of my army. For your information, I mention them below (7)

First of all you, then Bhishma, Karna and the always victorious in battle Kripa; Ashvatthama, Vikarna and the son of Somadatta, Bhurisrava; (8)

And there are many other heroes, all skilled in warfare, equipped with various weapons and missiles, who have staked their lives for me. (9)

This army of ours, fully protected by Bhishma, is unconquerable; while that army of theirs, guided in every way by Bhima, is easy to conquer. (10)

Therefore, stationed at your respective positions on all fronts, wherever the battle moves, all of you must stand firm and make sure that Bhishma, in particular, is protected on all sides.” (11)

Then Bhishma, grand old man of the Kaurava race, their glorious grand-uncle, cheering up Duryodhana, roared his lion’s roar, and blew a powerful blast on his conch horn. (12)

Immediately, conchs, kettledrums, cymbals, drums, and trumpets, blared forth a deafening clamour and the noise was tumultuous. (13)

Then, seated in a glorious chariot yoked with white horses, Krishna and Arjuna blew their celestial conchs: (14)

Krishna blew his conch named Panchajanya (won from the demon Panchajanya); Arjuna, his own called Devadatta (God Given); while ferocious, wolf-bellied Bhima blew his mighty conch called ‘King Paundra’. (15)

Prince Yudhishthira, son of Kunti, blew his conch Anantavijaya (unending victory), while Nakula and his twin brother Sahadeva blew theirs known as Sughosa (great Noise) and Manipushpaka (Jewel Bracelet) respectively. (16)

And the excellent archer, the King of Benares, and the great warrior Shikhandi, Dhrishtadyumna, Virata, and invincible Satyaki, Drupada as well as the five sons of Draupadi, and the mighty-armed Abhimanyu, son of Subhadra, all of them, O King, severally blew their respective conchs from all sides. (17-18)

And the uproar, echoing through heaven and earth, tore through the hearts of Dhritarashtra’s men. (19)

Now, Arjuna, son of Pandu, looking at the battle ranks of Dhritarashtra’s men arrayed against him, took up his bow as missiles were ready to be hurled, and said to Krishna, “Drive my chariot and stop between the two armies, (20-21)

And keep it there so that I can carefully see those warriors drawn up and eager for battle, whom I am about to engage with in this fight. (22)

I want to look at the well-wishers who have assembled on the side of evil-minded Duryodhana, and who are ready for the battle. (23)

After Arjuna had spoken, Krishna drove the magnificent chariot between the two armies, facing Bhishma, Drona, and the other great kings and said “Look Arjuna, from here you can see all the Kauravas assembled for battle.” (24-25)

Now Arjuna saw situated there in both the armies, fathers, grand-fathers, teachers, even great grand-uncles, maternal uncles, brothers, cousins, sons, nephews, grand-nephews, fathers-in-law, friends and well-wishers as well. (26 & first half of 27)

Seeing all those kinsmen present there, Arjuna was filled with deep compassion, and uttered these words to Krishna in sadness, (Second half of 27 and first half of 28)

“Krishna, at the sight of these kinsmen arrayed for battle, my legs weaken, my mouth is parched, a shiver runs through my body and my hair stands on end (Second half of 28 and 29)

My bow, Gandiva, slips from my hand, and my skin too burns all over; my mind is reeling, and I can no longer stand. (30)

And, Krishna, I see such omens of evil. No good can come from killing my own kinsmen in battle. (31)

Krishna, I do not desire victory, nor the pleasures of kingdom. Of what use is kingdom or luxuries, or even life itself, (32)

when for those whose sake we desire the throne, luxuries and pleasures – teachers, fathers, sons, nephews and even grand-fathers and great grand-uncles, maternal uncles, fathers-in-law, grandsons, brothers-in-law and other relatives – stand here arrayed on the battle-field risking their fortunes and lives? (33-34)

Though they want to kill me, I have no desire to kill them, even for the kingship of the three worlds, let alone for that of the earth. (35)

Krishna, what happiness can we hope for in killing the sons of Dhritarashtra’s men? Evil will surely cling to us, even though they are the aggressors. (36)

It would be unworthy of us to kill our own kinsmen. How can we be happy after the kill? (37)

Because their minds, blinded by greed, perceive no harm in destroying their own family, nor any crime in treachery to friends, why should not we, who know better, and can clearly see the harm accruing from the destruction of one’s family, think about turning away from this evil? (38-39)

Age-long family traditions and duty disappears with the destruction of the family; and when virtue is lost, lawlessness takes hold of the family. (40)

With the preponderance of vice, when the women of the family become corrupted; an intermixture of castes is the inevitable result. (41)

The intermixture of caste drags down to hell both those who destroy the family and the family itself. Deprived of their offerings of rice and water, the spirits of their ancestors also fall. (42)

Such are the evils brought about by those who destroy the family: because of an intermixture of castes, the age-long caste duties and permanent family customs become obliterated. (43)

Krishna, we often hear that men whose family duties have been abandoned, dwell in hell for an indefinite period of time. (44)

Oh what a pity! Though possessed with intelligence, we have set our minds to commission a great evil. Because of lust for the throne, and enjoyment, we are intent on killing our own kinsmen. (45)

It would be better for me if Dhritarashtra’s men, armed with weapons, killed me in battle while I was unarmed and unresisting. (46)

Having spoken these words, Arjuna, whose mind was heavy with grief on the battle-field, dropped his bow and arrows, and sank down into his chariot. (47)